BY STEVE COMUS

There are many things to think about when it comes to late season waterfowling compared to early or midseason bird blasting.

Some folks suggest that the birds are harder to bring down in the late season, due to heav ier protection provided by denser feathers, etc. I have not found that to be the case, however. When hit solidly with the right loads, waterfowl drop out of the sky, regardless of what time of year it is.

But there is no doubt that many birds during the late season have learned a lot by being shot at earlier on, and that they are more wary when it comes to being decoyed into shotgun range.

This means it is even more important to camouflage movement in the blind as much as possible, don’t over call and be patient. Some wary birds simply will not decoy in, so forget them and focus on those that will.

Certainly, weather and atmospheric conditions loom large during the late season, but gun fit and conditioning generally turn out to be the most important considerations.

The reason gun fit plays such an important role this time of year is that the hunters themselves tend to wear much heavier and bulkier clothing because of the cold.

The stock on a gun that fit well early last fall may be too long when the hunter wears several layers of insulated clothing. This may not sound like much on the surface, but it can affect where the gun shoots compared to where the hunter is looking.

In addition to problems like having the butt of the gun hang up on a heavy coat when mounting the gun for a shot, the actual point of impact of the pellets in the shot payload can change enough to turn a hit into a miss.

When point of impact is affected by length of pull, the result of a stock that is too long is that the point of impact will tend to be lower, while the result of a stock that is too short is that the point of impact will tend to be higher.

There is an easy way to check this. While wearing the entire waterfowling outfit, just go to a patterning board at a local range or take a large paper target with an aiming point of an inch or two to somewhere that it is okay to shoot and fire a round or two at 15 yards or so.

Look to see where the pattern is relative to the aiming point. The aiming point should be more or less in the middle of the pattern — a little bit high is okay, but not more than 60 percent of the pattern should be abov

e the aiming point. A 50/50 situation is good.

If the pattern is too low, try shedding one or two layers of clothing. If, after doing this, the pattern is back where it should be, then it is time to decide whether to wear less clothing on the hunt or shorten the length of pull by the amount indicated when the clothing was removed.

Some serious waterfowlers address this situation by having two different guns for the different seasons, or by having a longer recoil pad for early seasons and a shorter recoil pad for the late season.

The point is that if the gun is not shooting where the hunter is looking, then the chances of making good hits at varying distances go way down. Something to think about.

Another big item to consider for late season waterfowling is what I call seasoning the gun — getting it ready for the challenges of cold, freezing weather coupled with dirt and grime encountered on the way to and during the time in the blind.

For those using break-open guns like side-by-sides and over/unders, the most important thing is to keep dirt and crud from getting into the action when the barrels are open.

Crud buildup in extreme cases can prevent the gun from being completely closed, or when encountered to a lesser degree, grit can mar the finish on the monoblock and the inside of the receiver where the barrels fit. Keep those guns clean, at least on the inside.

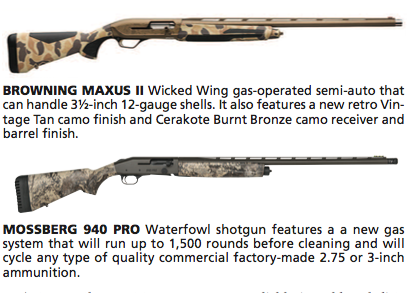

Autos are the most temperamental of the waterfowling gun designs because they require the performance of the ammo to cycle.

All of the three main types of semi-auto shotgun actions have their weak points when it comes to functioning flawlessly in really bad weather and when dirt and crud occur.

Gas-operated semi-autos can tend to function sluggishly or even malfunction if there is ice buildup in the action, around the bolt or in the area where the gas bleed off actuates the connecting rod (mechanism) to the bolt.

By nature, gas-operated semi-autos create carbon buildup around the point where the gas is bled off from the bore. With moisture and cold, this carbon gunk gets gooey and can even freeze.

When that happens, the gun generally will either not cycle quickly, or maybe not cycle at all. In other words, it can become a single shot until the frozen goo is removed.

When that happens, the gun generally will either not cycle quickly, or maybe not cycle at all. In other words, it can become a single shot until the frozen goo is removed.

Although they are generally more reliable in cold and dirty environments, both recoil-operated and inertia actions can be affected by ice and crud. Again, the situation can range from sluggish cycling to failure to cycle at all.

Hunters using semi-autos for cold weather late waterfowling often carry a spray can of some kind of de-icer. There are such products in the industry specifically designed to clear away both ice and crud, or there are automotive products that accomplish the same thing.

The bottom line is that keeping the action both clean and de-iced can keep it running smoothly in the blind.

Pump shotguns also can suffer from ice and crud build-up, but not as quickly because the hunter can always apply more elbow grease to cycle the action if it begins to freeze or clog.

Bottom line: to the extent possible, keep the gun clean, dry and free from ice. That alone will help assure that the gun will go bang when the birds fly into range.

Closing the waterfowl season on a strong note

BY TIM HOVEY

Like most of the western waterfowl hunters, I’ve also been anxiously awaiting the arrival of birds for this season. Bird presence in areas I hunt have been mediocre at best, with first light flights of limited birds and then nothing. This year’s California waterfowl season has definitely gotten off to a slow start.

Last season, with a firm determination to get back into hunting ducks after a lengthy absence, I had one of the best waterfowl seasons ever. I can clearly remember walking to the hunting spot and seeing thousands of birds in countless groups swarming the sky. The weather was picture perfect for duck hunting; cloudy, a little windy with a slight chance of rain. That opening day was like a dream for anyone even remotely interested in hunting waterfowl. The contrast between last year and this year is a tough pill to swallow.

With the bluebird weather and the lack of birds, I decided to further my understanding of waterfowl movement and duck presence in areas where they’ve been hunted for decades. We all know the old saying, “They fly south for the winter,” but I wanted to know more.

Let’s first look at how ducks are categorized across the U.S. The country is divided into four separate flyways: The Pacific, the Central, the Mississippi and the Atlantic. Of course, western waterfowlers hunt ducks throughout California, Nevada, Oregon, Washington and Idaho along the Pacific Flyway. When fall and winter temperatures start to drop, the birds began to migrate from the north to more temperate and mild temperatures in the south. But where are they coming from?

A 2017 study by the University of Minnesota and the California department of Water Resources used over 50 years of banding research to determine where birds were coming from, band to harvest. The report stated that 38% of the more common ducks like teal, widgeon, mallard, gadwall and wood ducks encountered in the Pacific Flyway came from Alberta, Canada. An additional combined 30% come from states in the northern west like Idaho, Montana and the Dakotas. In fact, per the study, 45% of the wood ducks that originated in Idaho were harvested by California hunters.

Other Canadian provinces, like the Yukon, British Columbia and the Northwest Territories, play into the annual north-south migration of waterfowl into the Pacific Flyway as well. However, knowing where these birds originate is only half the battle.

Cold weather, or perhaps the lack of cold weather, is a driving force behind waterfowl migration. When predicted winter cold fronts move through the north, the birds start their migration south. If that weather doesn’t materialize, or the northern habitats are stricken with drought, this heavily impacts duck numbers and their seasonal migration.

The crippling drought conditions that have plagued California for a decade or more can certainly play into low duck numbers during the season. Areas that once held thriving waterfowl habitat and flooded ponds needed for their wintering grounds, are frequently dried up for consecutive years, heavily impacting waterfowl migration patterns.

Continued drought conditions have even impacted summer waterfowl breeding areas to the north. A lack of water will reduce egg production, reducing overall bird numbers. When it comes to seasonal migrations, waterfowl depend heavily on precipitation, winter storms and water availability in both their summer and winter grounds.

Last week, I headed out to hunt a small parcel on private land I have access to. Previous hunts here this season have been dismal as far as bird numbers. As usual, an early morning flight with a few birds would give way to complete silence in the skies less than an hour after sunrise. This hunt would be different.

After jump shooting a handful of ducks on the way to our hunting spot, we were treated to consistent action throughout the morning. Overcast skies and windy conditions kept the birds moving, and I was finally able to scratch out my first limit of the 2021 waterfowl season.

It’s clear that changing environmental conditions do impact waterfowl movement. Across the board, this season has been far slower than last season, for me anyway. Following the California counts up and down the state, it appears that hunters are toughing it out and capitalizing where they can. The numbers in the northern part of the state do appear to be better than in the southern portion. But north or south, hunters understand that this season has been different.

As hunters, we understand that environmental conditions, including water availability will drive all levels of game abundance. Some seasons will be better than others. Good or bad, we should all be grateful with what each season brings us and enjoy our time outside with family and friends. And who knows, predicted late season storms may still bring amazing waterfowl hunting for those that stay at it and hunt to the bitter end.

I know I’ll be out there, hunting until the season ends.