BY STEVE COMUS

Production hunting rifles and the ammo they shoot, across the board, never have been as accurate and high performance as they are now. Credit the combination of computerized design and machinery with high-tech materials.

Throughout the last half of the 20th Century, hunting rifles that delivered 100-yard, three-shot groups of 1 ½ inches or better were considered “good enough.”

Granted, very many of them were more accurate than that, but 1 ½ Minute-Of-Angle (an MOA is roughly one inch at 100 yards) was the standard. During that time, for example, most Remington Model 700 centerfire bolt-action rifles would deliver groups around ¾-inch, as did a number of the Savage models.

That 1 ½ MOA standard created the concept that the longest shots on game should be around 300 yards. That meant that, all other things being equal, the rifle was capable of delivering shots within a 4 ½-inch area on the animal at 300 yards, which would mean kill zone in deer size or larger game.

Now, one MOA is generally considered routine, while custom and semi-custom rifles boast half-MOA or better. And it is not uncommon to find production rifles that shoot sub-MOA.

There have been very accurate rifles since the beginning of rifling hundreds of years ago. But the way their superior accuracy was achieved made them very heavy and not what today would be considered to be a “hunting” rifle.

That’s because those rifles had extremely heavy barrels that accomplished two things: (1) reduced barrel harmonics (whip) and (2) eliminated the negative effects of bedding (forces on the barrel and action from the way it is attached to the stock).

That resulted in a situation where the only limiting factors to accuracy were the ammunition and the shooter’s ability – and, of course, the quality of the barrel itself.

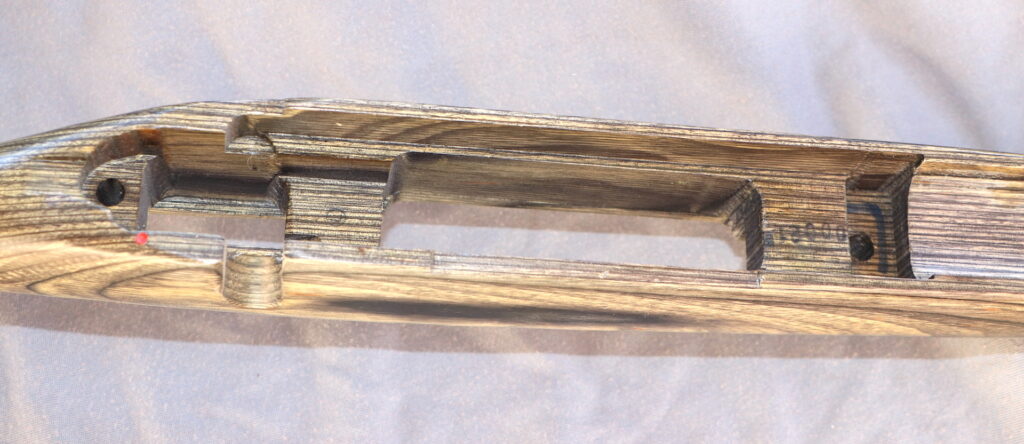

NO BEDDING materials were used for centuries on all guns, including bolt-action hunting rifles. This stock is inletted for the barreled action, and the barreled action is merely clamped into the stock by the bottom metal and the bottom of the action.

In today’s production hunting rifles, barrel technology via more precise drilling, rifling and alignment is such that lighter barrels can deliver better overall accuracy than before.

Couple that with advancement in improved bedding designs, and what comes out is a rifle in which the barrel harmonics and bedding forces are eliminated as negative factors (there are still barrel harmonics, but they can be controlled better than before.

Meanwhile, ammo makers continue to turn out more consistent ammunition – again a benefit of improved production machinery, improved designs and improved materials.

Although each of those factors can be the subject of dissertations, the point is that they exist and are having a combined effect that makes it possible for companies to deliver affordable, lighter weight rifles that are, overall, more accurate than before.

The bedding of bolt-action rifles can’t improve the inherent accuracy of a barreled action, but it can degrade it. For decades now, a common way to reduce any negative effects of bedding has been to bed the rifle so that the barrel doesn’t touch the forend of the stock (called free floating).

Any pressure from the forend on the barrel can affect the barrel harmonics in a way that changes the point of impact, and depending on how and where that pressure is, it also can change the point of impact as the barrel heats up.

For years, Remington shied away from free-floating the barrels on Model 700 hunting rifles, and instead designed the stocks so that the forend exerted a controlled amount of pressure on the barrel right where the forend ends. This served as a damper for the harmonics and worked well until the standard for accuracy went to and now even below a minute of angle.

As much as free floating barrels helped, it wasn’t the full answer. How the action is bedded in the stock also is critical to enhanced accuracy.

Initially, barreled actions were simply clamped into wood stocks with action screws fore and aft that used the bottom metal and the bottom of the action to clamp the action into the stock and hold it in place.

This alone meant that if the wood swelled or shrunk because of moisture, the rifle could lose its zero and put bullets as much as several inches farther apart than when the rifle was sighted in.

Wood and synthetic stocks can compress when squeezed hard enough, so some rifle makers used what was called pillar post bedding systems in which the action was squeezed together with the bottom metal and a “pillar” between it and the bottom of the action.

That meant that the action was bottoming out on the metal pillar so that it didn’t matter what the wood or stock material around it did. Metal on metal, both front and back, rendered any stock forces moot when it came to affecting the bedding.

Other methods of improved bedding included what is known as “glass bedding” where a form of fiberglass gel is placed at contact points in the barrel and action channels, and then the barreled action is squeezed tightly, forming the hardening gel precisely to the contours of the metal. Once set, the glass bedding created a solid rest for the action and shank of the barrel, again not precluding any negative side pressures.

As synthetic stocks became more popular and available, H-S Precision invented what is known as an aluminum bedding block. They made aluminum “blocks” contoured to fit the actions precisely and then built the bedding blocks into the fiberglass stocks when they were laid up at the factory.

With the advent of modularity in the AR platforms came what is known as the chassis rifle where there really isn’t a stock in the classic sense, but the barreled action is attached to a metal “stock” that serves as a chassis for the entire rig, with a forend way below the barrel and a rather skeletal metal and plastic buttstock.

This works really great for long-range shooting, but chassis rifles tend to be quite a lot heavier and bulkier that classic hunting rifles, which means they are clunky and a chore to heft around the hills.

Injection molded stocks are the most economical of the synthetic stocks to make, yet they tended to be not rigid enough to offer really solid bedding absent something like pillars or bedding blocks.

In recent times, however, stockmakers have figured out a way to include a much harder plastic (like the old glass bedding) into the stock when it is molded.

That has resulted in a low-cost stock that has the equivalent of pillar or glass bedding built right into it – accuracy and at a savings of weight. Hence, those stocks tend to be lighter, resulting in a hunting rifle that is both lighter and as accurate as the barreled action allows. Best of both worlds.

Yes, production rifles have come a long way and are better than ever.