BY LARRY BROWN

We were on my 7-day Royal Star charter in October, 2020, enjoying a very good bite on 15- to 35- pound bluefin and yellowfin tuna. On one particular stop anglers were enjoying fast action on a school of 12- to 18-pound yellowfin. The crew was very busy helping anglers and processing the fish to assure the highest quality standards famous on the Royal Star and during the melee nobody noticed the small longfin tuna on the deck. It wasn’t until the fish were being moved from the RSW system to the onboard weigh station and into the icy dockside totes that Captain Tim Ekstrom held up the little fella and said, “Wow, we caught an albacore.” Probably a lot of anglers and many of the crew members had never seen an albacore, explaining the delayed identification, in addition to the frenzied pace of fish coming over the rail. Tim sent me a photo of the long- finned fish that evening.

Look at the photo. Is there any doubt about the species of tuna we caught? Tim said, “No doubt whatsoever.” But one of my NOAA biologist friends heard about the catch and wondered, “What could a lone albacore possibly be doing with a school of straight yellowfin tuna.” Any albacore caught these days creates a buzz in the sportfishing industry and probably among the scientific community as well.

Fisherman’s Processing retained the carcass for Owyn Snodgrass, NOAA Fisheries Scientist specializing in Pacific Tunas. Scientists are inherently curious about anomalies. After Fisherman’s Processing delivered the carcass to the Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, Owyn stated that the fish had the external appearance of an albacore but the liver appeared more like a yellowfin tuna. He said, “The long pectoral fins and external color looked like an albacore but the color and shape of the liver from that fish screamed yellowfin… not albacore. But external coloration can be misleading and pectoral fin length can vary. So I tested the DNA, which proved this fish was indeed an albacore.”

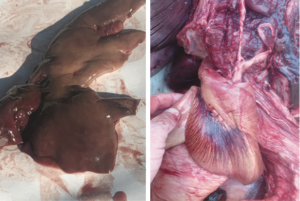

Owyn shared the actual image of the liver from our subject long-finned tuna, (see photo) along with an image from an albacore he had on file.

Owyn points to the lack of striations or counter current heat exchanging veins in the liver on the left. Albacore normally have very obvious veins (photo on right) that run through their liver to help them retain their internal body temperature, which allows them to inhabit cooler water than yellowfin tuna.

He added, “Bluefin and bigeye tuna also have the counter current heat exchanging veins or striations in their liver for the same reason… by looking at the liver it’s very easy to see the differences.”

Tim Ekstrom speculated the wrong gut sack and liver may have been kept and given to NOAA. I wonder if our albacore lost it’s typical liver striations because it had been swimming around in warmer water, more preferred by the yellowfin tuna family it had adopted. Birds of a feather flock together, and fish of a fin swim together for all the evolutionary reasons starting from the time they are hatched.

But a fish separated from its birth species is more viable as predator and prey if it bands together in a school, even one of another species. Will its genetics be lost forever or are there examples of cross species spawning and fertilization?

So how can the occasional angler identify one tuna from another? I’ve been on many trips when anglers ask, “Is that a yellowfin tuna or a bluefin tuna?” I have heard anglers and deckhands argue if a fish is a bigeye or a yellowfin.

Mr. Snodgrass also shared, “Over the past 3 years there have been several other tuna that anglers misidentified off of Southern California. I collected 5 alleged ‘bigeye’ tuna that were all actually funny looking yellowfin tuna with slightly longer-than-normal pectoral fins. We confirmed these identities with DNA from those fish.”

Sportfishing captains like Tim Ekstrom with 35 years experience running boats and catching tens of thousands of different tunas have no problems identifying these fish. But private boaters and anglers on sportboats are frequently uncertain if the fish they just landed is a yellowfin, bluefin or bigeye. So how are anglers and crew members able to identify different tunas?

In light of the confusion over tuna identification, Owyn said he and his fisheries colleagues collaborated to put together a new publication titled: Tuna Species of the U.S. West Coast-A Photographic Identification Guide. Liana Heberer, Owyn Snodgrass, Heidi Dewar and David Itano created the guide published by NOAA.

Liana Heberer took the lead role in this NOAA booklet, so I asked her to help anglers and crew members with the definitive guidelines for identifying the common tunas we catch off of California and the northern Baja. Ms. Heberer is a fisheries biologist with the Institute of Marine Sciences at UC Santa Cruz working with NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center. She focuses on highly migratory tuna, billfish and sharks.

Liana explained their motive in making the ID Guide. “We have worked and fished for many years with the sportfishing community and we made this ID guide inspired by our dockside sampling work. Some species were harder to identify dead after retrieval from the RSW than live fish with fresh color, so we made a point to include both fresh and post-mortem color photos. We also noticed how many anglers were asking us questions about tuna biology and identification while down at the docks, so we hope the summarized information for common West Coast species is useful for anglers and scientists alike.”

She added, “We also want to thank the many captains, crew and landing personnel in San Diego who have collaborated with us and shared their knowledge along the way, and Chris Wheaton (@fishids), David Itano, and Kurt Schaefer for sharing their stellar photos”.

Sections of the ID guide are shared below, while the entire color hardcopy ID guide booklet is available for free. Booklets can be picked up at the Sportfishing Association of California office in Point Loma (5060 N. Harbor Dr #165, San Diego, CA 92106), mailed by request (contact liana.heberer@noaa.gov), or downloaded digitally for use on mobile or desktop at https:// repository.library.noaa.gov/view/ noaa/23154I. I highly recommend every private boater and every angler retain one of these booklets for on-board reference. It’s FREE.

Glossary

Corselet: a zone or area of scales behind the head and the pectoral fins of certain tunnies, albacores, bonitos, and frigate mackerels

Lateral line: a visible line of sensing organs located along the midline of the body that are used to detect vibrations and pressure in the water

Median caudal keel: a lateral ridge on each side of the caudal peduncle used in stabilization and drag reduction during swimming in some tunas; anterior to two oblique caudal keels on the caudal fin

Striations: blood vessels allowing for counter-current heat exchange enabling warm viscera

Urogenital pore: a small ventral opening anterior to the anal fin used to excrete waste and reproductive fluids into the surrounding water

Endothermic: ability to maintain body tissue temperature warmer than ambient water temperature

Pelagic: occurring in the open ocean and in the upper and mid-layers of the water column

Epipelagic: upper strata of the ocean where enough visible sunlight penetrates the water column for photosynthesis to occur, about 200 meters deep; also known as the “sunlight zone”

Mesopelagic: middle strata of the ocean below the epipelagic zone, starting around 200 meters deep; also known as the “twilight zone”

Thermocline: abrupt transition layer between warmer mixed water at the surface and cooler deep water

Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis)

Description: Deep body profile with skin transitioning from titanium blue back into lighter blue; dark blue, almost black pectoral fin is shorter than head length; lower sides and belly are silver with consistent lateral spots and faint vertical lines; second dorsal fin is reddish-brown and anal fin is edged with black.

Other common names (language or location): Atún aleta azul or atún rojo (Spanish), honmaguro (Japanese)

Size and reproduction: Pacific bluefin tuna reach sexual maturity around 150 cm FL (5 ft.; age 4-5 years), as early as age 3 in the Sea of Japan. Although Pacific bluefin can reach 300 cm FL (9.8 ft.), those found off the U.S. West Coast generally range from 40- 200 cm FL (1-7 ft.; 40-350 pounds) and are not reproductively mature.

Habitat: Pacific bluefin tuna are epipelagic, spending the majority of time within the surface mixed layer and making extensive vertical dives from the surface up to 1,500 m5. Pacific bluefin spawn from April to July in the Western Pacific Ocean (WPO) off eastern Chinese Taipei and the Ryukyu Islands, and July to August in the Sea of Japan. An unknown portion of the population migrates to the EPO around ages 1-3 to forage before returning to spawning grounds in the WPO. Pacific bluefin generally school in similar size cohorts and adults are hardy and cold tolerant, entering warm waters only for spawning.

Diet: Small pelagic fish and crustaceans, and squid.

Fishing: Purse seine, longline, troll, gillnet, harpoon, hook-and- line, spear gun. Bluefin are highly valued for sushi and sashimi.

West Coast seasonal range: Common in coastal and offshore waters from U.S.-Canada border to U.S.-Mexico border, although seasonal distribution is largely dependent on water temperatures and bait availability. Juveniles move into Southern California from Baja California, Mexico in spring, then to central and northern California by early fall. Then back into the Northern Baja for the winter.

Yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares)

Description: Dark blue back with abrupt shift to bright yellow and silver sides; yellow fins and finlets are lined with a black edge; lower sides are marked with consistent lines and spots in almost vertical lines.

Other common names: Atún aleta amarilla (Spanish), ahi (Hawaii), kihada (Japanese)

Size and reproduction: Sexual maturity is generally reached around 69 cm FL (2.2 ft.) for males and 96 cm FL for females (3.1 ft.; age 2 years).Yellowfin tuna can grow up to 200 cm FL (6.5 ft.), but fish around 60-150 cm FL (2-5 ft.) are most common off the U.S. West Coast.

Habitat: Yellowfin tuna are a tropical species restricted by a temperature range of 64°-86° F and they rarely venture into cooler waters3. They are found above and below the thermocline based on oxygen availability and temperature gradients and dive up to depths of 1,600 m10. Yellowfin are found seasonally in Southern California, however this is only a portion of the total population distributed across the Pacific Ocean.

Diet: Small fish, pelagic crustaceans and squid.

Fishing: Purse seine, longline, troll, hook-and-line, handline, spear gun. Yellowfin are important commercial targets for the fresh, frozen and canned industries. West Coast seasonal range: Common in coastal and offshore waters from central to southern California and Baja California, primarily during summer months with warmer water temperatures. Found year round in southern tropical waters.

Bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus)

Description: Metallic dark blue back with faint lateral blue band on live fish; skin gradually transitions through silver blue to yellow to pinkish-silver; anal finlets are dark and second dorsal and anal fins are light yellow; bigeye closely resembles yellowfin tuna at various size classes, but the most distinctive feature is a larger eye and a deeper body profile than yellowfin tuna.

Other common names: Atún patudo (Spanish), ahi (Hawai’i), mebachi (Japanese)

Size and reproduction: Bigeye tuna reach sexual maturity around 100-130 cm FL (3-4 ft.) and can exceed 200 cm FL (6.5 ft.), but those found off the U.S. West Coast average around 80- 100 cm FL (2.6- 3 ft.).

Habitat: Bigeye tuna are a tropical species found in epipelagic and mesopelagic wa- ters with distribution largely driven by thermocline depth and temperatures of 56°-85° F. Bigeye forage on the deep scattering lay- er in cool deep water during the day. They are known to aggregate around anchored or floating fish aggregating devices (FAD) and mix with schools of yellowfin or skipjack tuna.

Diet: Small pelagic fish, crustaceans, and cephalopods.

Fishing: Purse seine, longline, troll, hook-and-line, FAD fishing. Bigeye are caught in large numbers in Hawai’i and Pacific island nations, as they are valued for sushi and sashimi.

West Coast seasonal range: Occasional in coastal and offshore waters in central to southern California and Mexico if waters are warm enough, with optimal temperatures around 63- 71°.

Albacore tuna (Thunnus alalunga)

Description: Metallic dark blue back with faint lateral blue band along the side of live fish; skin gradually transitions through silver-blue to silver-white; anal finlets are dark and second dorsal and anal fins are light yellow; the most distinctive feature is a very long pectoral fin and the white edge of the caudal fin.

Other common names: Atún albacora (Spanish), tombo (Hawai’i), binnaga (Japanese)

Size and reproduction: North Pacific albacore can grow up to

140 cm FL (4.5 ft.) and reach sexual maturity around 83-93 cm FL (3 ft.; age 4.5 years) for females and 78-93 cm FL (2.5- 3 ft.) for males.

Typical sizes off the U.S. West Coast range from 30- 121 cm FL (1-4 ft.; 20-80 pounds).

Habitat: Albacore is a cool-water species inhabiting offshore waters between 56°-66° F. They tend to concentrate along thermal oceanic fronts, like the Kuroshio Current, where they are caught in abundance. Albacore are known to migrate across the entire North Pacific Ocean within water masses instead of across temperature and oxygen boundaries.

Diet: Schooling fish stocks such as sardine, anchovy, rockfish, and squid.

Fishing: Longline, live bait hook-and-line, trolling, purse seine. Albacore is the only tuna with pure white meat, making it an extremely valuable commercial target in the U.S., primarily for the canning industry.

West Coast seasonal range: Common in coastal and offshore waters from the U.S.-Canada border to the U.S.-Mexico border and Northern Baja. Albacore favor cooler water temperatures and are more common in the most northern range of their west coast distribution, off Oregon and Washington.