By Mike Brasher, PhD; Dan Smith, PhD; John Coluccy, PhD

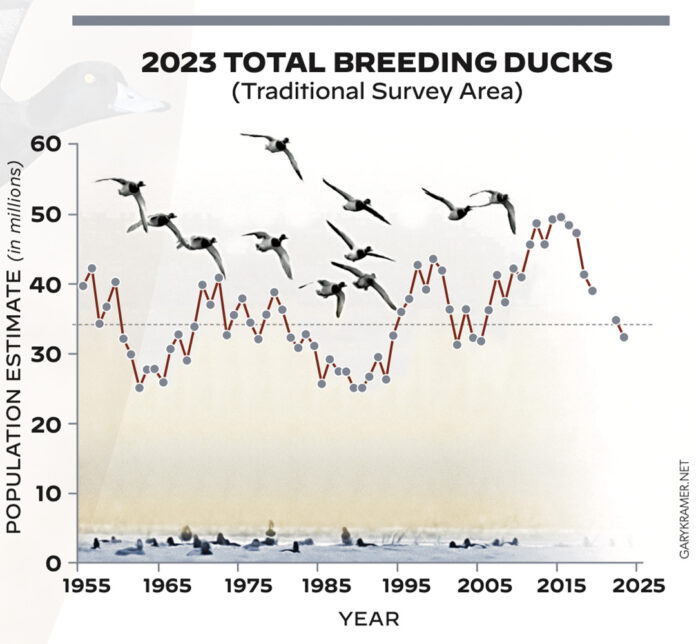

SACRAMENTO– For most waterfowl biologists and hunters, some of this year’s waterfowl survey results, which were released in mid-August by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), came as an unpleasant surprise. In the spring of 2022, following years of prairie drought, the number of ducks arriving and settling on the breeding grounds was lower than it had been since 2005. However, improved wetland conditions in many areas led biologists to believe that those ducks would have good breeding success overall, resulting in more ducks in the fall flight and more ducks returning to the breeding grounds in 2023. It is understandable, then, if waterfowl enthusiasts were surprised when many of this year’s breeding duck populations had, in fact, declined.

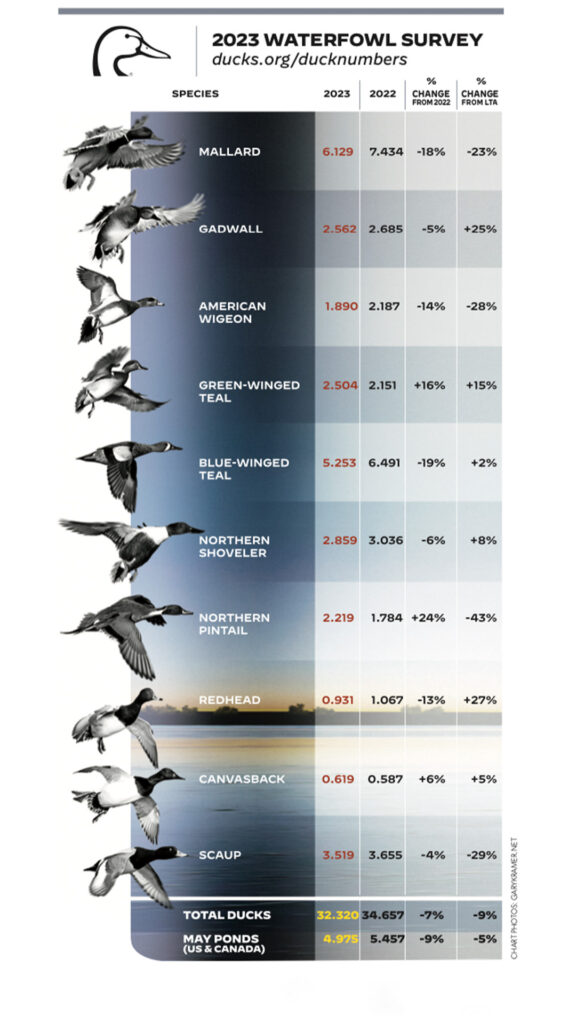

These numbers come from two survey regions: the traditional survey area and eastern survey area. The traditional survey area accounts for 75 to 85 percent of total estimated duck populations and encompasses breeding habitats from Alaska to western Ontario and south to the Dakotas and Montana.

Waterfowl harvested in the Pacific Flyway originate primarily from Alaska, British Columbia, Alberta, and local populations in Washington, Oregon, and California. Total breeding ducks in these areas in 2023 were estimated at 14.7 million birds, 7 percent below the 2022 estimate and 15 percent below the long-term average. A major cause for this year’s decline was a 50 percent drop in estimated duck numbers in Alaska.

Results from southern breeding areas in the flyway were mixed. Duck populations in Washington declined by 7 percent, while those in Oregon declined by 43 percent. Record snowfall and above-average rain improved habitat conditions across much of California, leading to a 30 percent increase in the number of breeding ducks in the state. Nevertheless, effects of the recent multi-year drought continue to be felt, as the breeding duck population in California remained 8 percent below the long-term average.

Five species account for over 80 percent of the annual duck harvest in the Pacific Flyway—mallards, green-winged teal, American wigeon, northern shovelers, and northern pintails. Mallard numbers across Pacific Flyway breeding areas declined 11 percent from 2022 and were 19 percent below the long-term average. Green-winged teal increased 20 percent over the previous year’s estimate and the long-term average. American wigeon and northern shovelers declined by 20 and 24 percent, respectively, and both were below their long-term averages. Pintail estimates were similar to 2022 but remained 43 percent below the long-term average.

Sharp declines in duck populations in Alaska survey regions were largely unexpected, as habitat conditions last year were reported to be excellent. Insights from partner biologists suggest that cooler-than-average spring temperatures and above-average snow and ice cover may have challenged survey timing in some regions and caused a redistribution of breeding ducks. Paired with declines in survey results across Alaska were increases in the Yukon, Northwest Territories, and northern Alberta. Warmer conditions arrived suddenly, causing flooding in interior Alaska as the Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers swelled.

Overall, observers expected good to excellent production in Alaska, the Yukon, and the Arctic Coastal Plain, and fair to poor production across Boreal regions of the Northwest Territories and northern Alberta.

Habitat conditions improved in Washington, Oregon, and California this spring. Heavy rains provided some drought relief in Washington, while excellent snowpack in Oregon recharged eastern basins after three years of dry conditions. Record mountain snow and abundant winter rain in California recharged most reservoirs to above-normal capacity and provided ample water for managed wetlands and rice production in the Central Valley. Waterfowl production in southern breeding regions was expected to be good to excellent, which should have added young birds to the fall flight and improved hunting prospects. However, water woes continue to plague other critical habitats for waterfowl, including the nation’s first waterfowl refuge, Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, which faces its fourth year of limited or no water.

Despite declines among several species and in many survey regions, waterfowl populations remain healthy overall relative to historical trends. Conservation is indeed a long game, and Ducks Unlimited’s decisions on where and how to protect priority waterfowl habitats are not based on a single year’s data.

If there’s one thing we’ve learned from decades of tracking and discussing waterfowl populations, it is that we rarely encounter years in which populations and habitat conditions are good across all breeding areas. Thus, keeping the table set through habitat conservation programs across all four flyways is a necessity. Improved habitat conditions on some landscapes this spring were conducive to average to excellent waterfowl production, while others continued to struggle with dry conditions and likely had fair to poor production. Although we shouldn’t expect a bumper crop of young ducks in the fall flight this year, there should be enough to keep us optimistic while enjoying our time with family and friends in the blind

For more information, visit Ducks.org